Written by Lisa Chedekel, chedekel@bu.edu

(Boston, Mass. – Boston University) -- Some of the wounds of war are invisible to the untrained eye: traumatic brain injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder, and illnesses traced to chemical exposures, to name a few.

(Boston, Mass. – Boston University) -- Some of the wounds of war are invisible to the untrained eye: traumatic brain injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder, and illnesses traced to chemical exposures, to name a few.

These injuries, which affect hundreds of thousands of veterans of the first Gulf War and the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, have been compounded by delays and controversy in recognizing, treating and compensating the veterans who suffer from them, according to Boston University Law School and Boston University School of Public Health experts and veterans' advocates who spoke at the annual Pike Conference, Oct. 29, 2010 in Boston.

"The VA's come a long way in the last few years, but there is still a lot of work that needs to be done," said conference panelist Paul Sullivan, a Gulf War veteran who heads the non-profit advocacy group Veterans for Common Sense. "We need more research, more treatment options, more doctors and mental health professionals… We [also] need facts and figures about the wars."

Sullivan joined fellow veteran Anthony Hardie and a line-up of BU School of Public Health professors at the conference to discuss the continuing challenges in research and treatment for troops who served in the 1991 Gulf War, as well as those now returning from Iraq and Afghanistan.

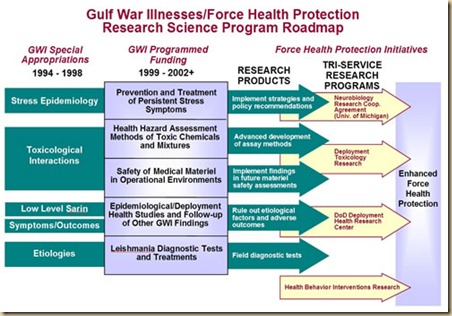

Chief among those challenges has been a 20-year battle, waged by veterans of the Gulf War, to get recognition and treatment for a cluster of debilitating symptoms known as Gulf War illness. Two years ago, a scientific panel directed by Roberta White, the conference keynote speaker and chair of the BUSPH Environmental Health Department, issued a landmark report affirming that neurotoxic exposures are causally associated with Gulf War illness. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has since agreed to re-examine the disability claims of Gulf War veterans.

"So much time was squandered," said Hardie, who serves on the scientific panel. He said he and other veterans were told for years, "'There's nothing wrong with you guys. It's all in your head.'"

He called White "one of our leading champions" in studying the causes of Gulf War illness.

BUSPH faculty members spoke of the need to ensure that the new generation of veterans receives prompt treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], traumatic brain injury, and mental-health problems.

Michael Grodin, professor of health law, bioethics & human rights at BUSPH and of family medicine and psychiatry at BU School of Medicine, said he was especially concerned about troops with PTSD and other mental-health problems being re-deployed multiple times into the war zone. He said that while there has been progress in understanding PTSD, "I think we need to utilize many treatment approaches."

George Annas, chair of health law, bioethics & human rights at BUSPH and a professor at the BU schools of law and medicine, noted that the military is grappling with an increase in the suicide rate among active-duty soldiers. Recently, the Army announced two major research project aimed at trying to understand risk factors and examine which suicide-prevention programs are successful.

"What intervention programs work? We don't know much about that," Annas said. "In this case, we're back where we were with the Gulf War syndrome, in 1992 -- we recognize there's a problem, and now we need to figure out what to do about it."

Leonard Glantz, a professor of health law, bioethics & human rights, said suicide prevention is difficult in both civilian and military life, and that identifying risk factors among soldiers is challenging because the number of suicide cases is relatively small.

Sullivan's group, which has battled for data from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, calculates that the VA's Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan patient count will reach 1.5 million by the end of 2014. Data obtained by the group shows that as of June 30, 2010, the VA had treated 594,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans -- up 29,000 from the previous three months. Of those, 295,000 were diagnosed with at least one mental health condition.

Hardie encouraged BU researchers to apply for available federal funding to study effective treatments for injured veterans. (http://cdmrp.army.mil)

"We've had a lot of success over 20 years," he said, "but 20 years is a long time to wait for health care."

Annas said BUSPH faculty members hope to continue working with veterans' advocacy groups on research and ethical issues.